The following article by Charles Hartley was published in two parts beginning on 9 August 2015.

It is combined here into one article.

We've written about Paroquet Springs before, and for those who don't recall, it was a mineral springs spa located just east of Shepherdsville near where the Paroquet Springs Conference Center is located today. The spa really got its start when a Frenchman named John D. Colmesnil saw its potential in the early 1830's.

Reuben Morgan, a Shepherdsville attorney, was living on the place in 1826, and made some minor improvements with the help of some of the town folk, including opening up a way from the town and erecting a structure over the spring with the hope of promoting the medicinal waters. However, he gave up his efforts, and moved to Meade County in 1833.

It was about this time that John D. Colmesnil became interested in the place as a retreat for his wife while he traveled on his various businesses. As we will see later, he gained control of the site around 1837, and moved there the next year.

It didn't take long for him to put things in order to welcome the public to his new spa. In 1839 he advertised in the Louisville Daily Journal that "The improvements are all new, neat and comfortable and room sufficient to accommodate 200 to 250 persons." Three years later a notice was printed in The Times-Picayune of New Orleans proclaiming its fine qualities.

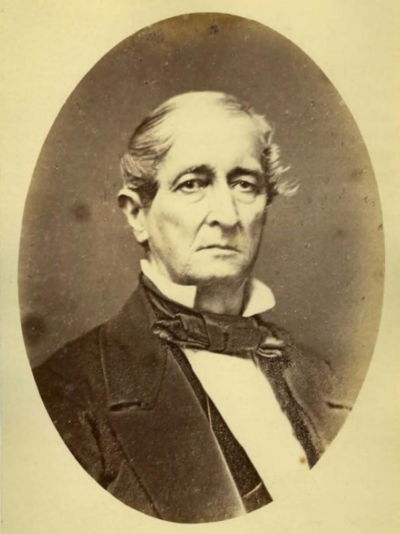

So who was this man who could so quickly turn a failed operation into one whose qualities were proclaimed across the South? The best place to begin is with his birth in 1787 and early childhood in Saint-Domingue, what we know today as the nation of Haiti.

John's father, Louis Gabriel de Colmesnil was related to the old French nobility. He resided in the mountains, near Saint-Marc, and held two plantations on the plain along the Artibonite River in Saint-Domingue which was under the control of France at that time. He cultivated sugar, cotton, indigo and coffee, using the labor of more than 2,000 slaves.

A slave insurrection broke out in 1791, and Colmesnil's neighbors came together on his mountain-side plantation, constructing a fortification for their safety. Fearing an imminent attack, the men hid their silver plate, burying it between two large mahogany trees in the yard, with the hope of recovering it later.

After a desperate resistance the place was taken by storm, and all who did not make their escape, including women and children, were massacred. John's mother, three sisters, and two brothers were among those who died. His wounded father was carried further into the mountains by a few of his faithful servants who stood by the family in opposition to the insurrection. John was saved by his nurse who took him with her family and hid in the mountains.

After a short time, both parties made their way to Saint-Marc where they were reunited. Although badly wounded, John's father chartered a vessel owned by Stephen Girard who often carried Colmesnil's produce to the United States. The vessel was loaded with all that he had stored in warehouses in town and, together with more than twenty of his servants who feared remaining behind, he and his son boarded, bound for Philadelphia.

Colmesnil sold his cargo in Philadelphia and moved to a small port community near Trenton, New Jersey. He remained there on a small farm until about 1800. Then, seeking a better climate, he moved to Georgia, near Savannah, where he developed a cotton plantation and a large garden from which he supplied the city with vegetables. He took with him such of the servants who wished to go. John's faithful nurse and family were freed, and remained in Philadelphia.

By 1804, John was 17 years old, and joined the Bolton shipping-house in Savannah as a clerk. He soon demonstrated his skills, and was given the responsibility of supervising his firm's cargo on several trips to the West Indies. On one of those trips, he revisited the place of his birth, and attempted to recover the hidden silver left behind by his father. Although he was able to secret the pieces inside bags of coffee, by the time everything reached the port, the silver had disappeared again.

On another trip, he went to Havana with a cargo of flour. At that time the import duty on flour was extremely high, and almost everyone attempted to avoid paying as much of it as possible. But after Colmesnil had managed to sell his entire cargo, the authorities discovered the failure to pay the duty, and confiscated the vessel, and arrested Colmesnil and his captain, putting them in the Moro Castle dungeon.

He remained there for a month, before a chance encounter with Don Vivas, the Spanish Captain-General, secured his release. Don Vivas was a classmate of John's father. John had a severe case of fever from his imprisonment, and was nursed back to health in the home of his rescuer until he could safely return home.

About 1808, he returned to his father's home in Georgia. His father soon died, leaving a will that freed all of the remaining servants, and providing each one with funds to start a new life. However, Georgia law made it impossible to free them there, so John worked the plantation for another year to raise the necessary money to move everyone to either New York or Philadelphia where his father's wishes could be fulfilled.

This task completed, John sold the plantation in Georgia. Then in 1811, he decided to visit the families of John and Louis Tarascon, husbands of two of his cousins, who lived in Louisville. At 24, he'd already had adventure aplenty, which brought him a clearer understanding of the importance of loyalty, and the value of being well-trusted. These would often stand him in good stead in the years to come.

The sale of his Georgia plantation had provided him with the necessary capital to seek new opportunities, and his visit to Louisville opened his eyes to the possibilities here.

The Tarascons operated a grist-mill at Shippingport, at the Falls of the Ohio, along with their shipping enterprises between Pittsburgh and New Orleans; and Colmesnil surely learned a great deal about opportunities along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers from them.

That December he took passage on a barge leaving Shippingport for New Orleans. On the 16th they were at New Madrid on the Kentucky Bend of the Mississippi River when the first of the major earthquakes struck that area. The barge's boatmen refused to continue the journey southward, fearing for their lives. Sensing an opportunity, Colmesnil bought a large flatboat, loaded it with flour, whisky, and whatever else he could find, and hired some Canadians who were present and willing to venture the trip to New Orleans.

The boat arrived safely in New Orleans, and Colmesnil made a tidy profit. The next summer, he returned to Natchez by boat, and then by horseback through the wilderness back to Kentucky.

Back in Louisville, he went into business with the Tarascons, making trips for them and trading for the company. He also went into the dry-goods business with Edward Tyler and Isaac Stewart for a time, and later with John A. Honore whose daughter Elodi he married about 1815.

It was also during this time that he frequently took barges to New Orleans in the fall and returned in the following spring. He made the shortest time on record then with a barge, which was sixty-three days.

After Elodi's death in 1820, Colmesnil went into the steamboat business. At various times he owned as many as six different steamboats. They all did profitable business, and he rapidly became one of the wealthiest merchants in Louisville. He owned the largest warehouse in Louisville for a time.

In 1826 he married Sarah Courtney Taylor, daughter of Army Major Edmund Taylor.

During these years he took an active part in government, first as a Louisville trustee from 1820-1827, and then as a member of the first City Council in 1828.

In 1825, when the private Louisville and Portland Canal Company was chartered, Colmesnil was a member and stockholder. And in 1830, he was one of the original trustees of the second church of St. Louis in Louisville. In 1834, Colmesnil was again elected Louisville councilman, and that same year he was involved in helping to raise funds to establish the Bank of Kentucky.

But, difficult times were just ahead. Following rises in interest rates across the nation in 1837, an economic panic caused prices of raw goods to fall sharply. People who had borrowed heavily to finance growth and improvements were forced to declare bankruptcy, and men like Colmesnil who were often the lenders suffered heavy losses.

He also suffered significant losses when a New Orleans firm failed, leaving Colmesnil with about $150,000 of debt. The remarkable thing is that despite these heavy losses, over time Colmesnil was able to repay every debt, dollar for dollar; although it cost him greatly in loss of properties.

It was at this same time that he was investing in the Paroquet Springs property. To prevent its loss to pay outstanding debts, he employed a legal fiction by having his good friend, James Guthrie purchase it as trustee for Sarah Colmesnil, using her husband's money.

Colmesnil and Guthrie had been good friends for many years, and each trusted the other explicitly. When Guthrie became United States Secretary of the Treasury, he hired Colmesnil to supervise shipments of large amounts of silver for the treasury department, knowing that he could be trusted with the task. One such shipment was reported to be valued at $1,750,000.

Meanwhile back at Paroquet Springs, Colmesnil continued to make improvements throughout the 1840's and 1850's, and the spa was a major attraction, especially considering the lack of good roads. Thus when the L. & N. railroad began its construction, and was to pass between Shepherdsville and the spa, it appeared that business would prosper even more.

Then came the Civil War, and everything changed. Union soldiers were camped on his property while stationed at Shepherdsville to protect the railroad bridge. They tore down most of his buildings, and cut down many of his trees: but still he remained there, too much attached to the place to leave it. In the last few years of his life, he had become so much attached to the place and so used drinking its waters that he felt he could not live any where else.

After the war, Colmesnil's health was so poor that little effort was made to return the spa to its former glory, and in the spring of 1871 he sold the Paroquet Springs property, and moved back to Louisville where he died on July 30th.

Shortly before he died, the spa reopened under new management, with new facilities. It's revival would be short-lived however, as the new hotel burned in 1879, following years of financial difficulties. The grounds would continue to be used for parties and picnics well into the 1900's.

Throughout his life, John D. Colmesnil was considered the personification of honesty. Of him it was reported that "He knew no guilt and harbored no deceit. His honest face mirrored his honest soul, and those who saw the one knew the other." A good way to be remembered.

Follow this link to a more detailed description of the life of John D. Colmesnil. Also see Audrea McDowell's article on "The Pursuit of Health and Happiness at the Paroquet Springs in Kentucky" for more details on Colmesnil's Shepherdsville home.

Copyright 2015 by Charles Hartley, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved. No part of the content of this page may be included in any format in any place without the written permission of the copyright holder.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/memories/colmesnil1.html